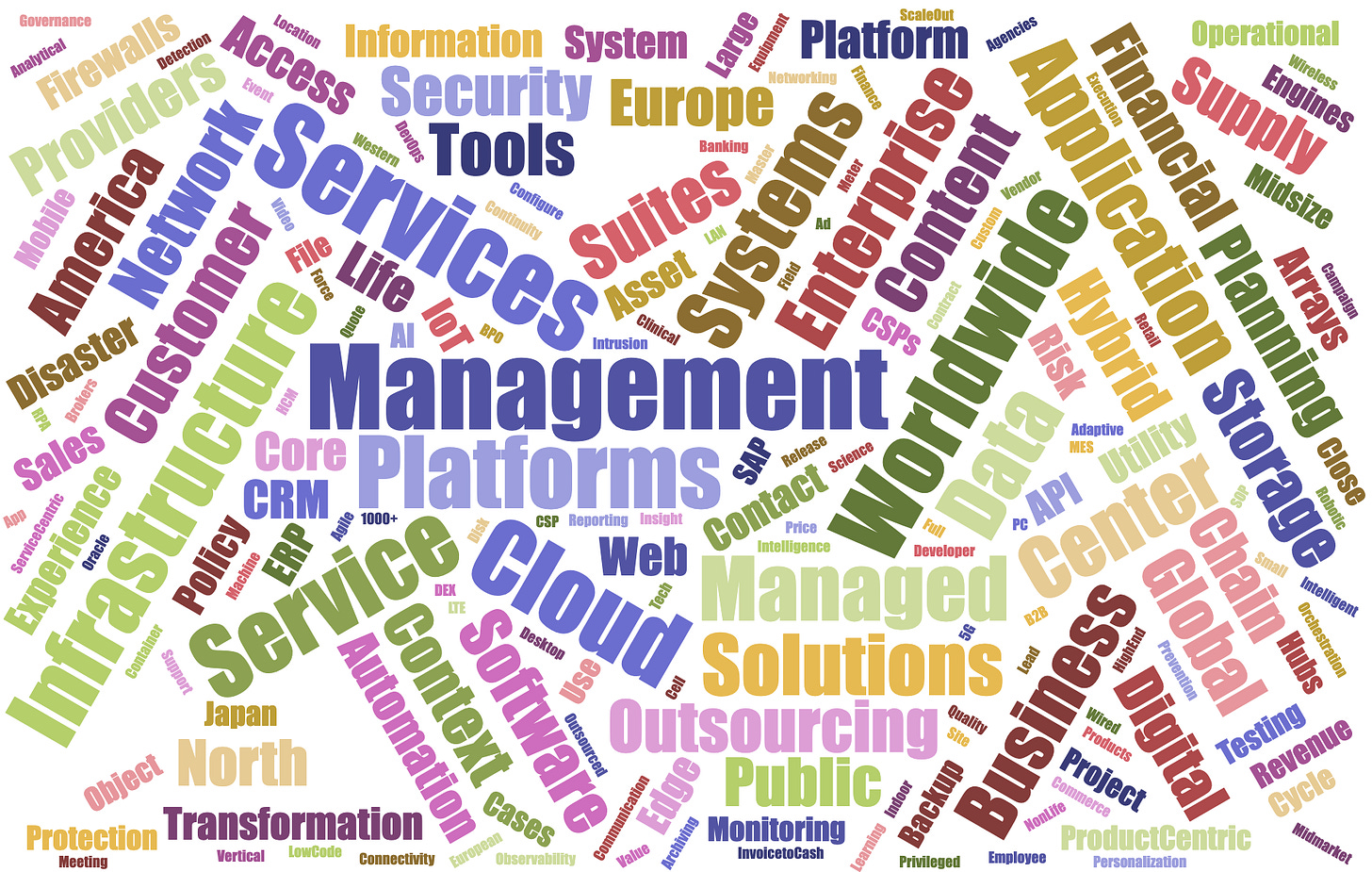

Word cloud of all Gartner “Magic” Quadrant Categories, Jan 2024

There’s one word the B2B software industry seems to love most.

Management - the act or art of managing : the conducting or supervising of something (such as a business)

However, in the enterprise software context, I’d argue we should use this definition.

Management - the activities and responsibilities involved in conducting a business process or project

Its utility and fraught nature come from its nebulous use. By tacking on the word to the end of any business concept, you’ve created an entire category of software to potentially sell:

Is this a bad thing though?

Business complexity necessitates complex software. Branding software as “management” creates a shared understanding of a problem between the seller and the buyer, and lumping the complexity of a particular domain into the idea of “management” helps move sales discussions forward.

But yes, it is bad.

This nebulousness represents what’s broken at the core of the software itself, as well as the processes to buy and implement it. By avoiding the use of the term altogether, maybe, we (those of us building, selling, and buying B2B software) can collectively create better outcomes for businesses and the humans within them.

The Buying Journey

Picture an aspirational manager who is considering purchasing “management” software for their team.

This person is a typical white-collar worker trapped in the unglamorous world of execution - actually doing the work. They must fabricate a simple reality for leaders while dealing with rote challenges and mistakes of junior team members. Their impetus for a software purchase comes either from frustration, comparison to other companies, or improving the bottom line while also covering the all-important digital transformation initiatives pushed by their leaders.

With aspirations of true organization change, the manager eagerly considers their options, begins researching their competitors, reads analyst reports, taps their network, and engages with sales reps1. They create a group of stakeholders to help with the decision, conduct long RFP processes, and usually decide on an established vendor.2

Over the course of this process, before any software is rolled out and hearts and minds are won, the battle has usually already been lost.

The Argument for Value Leads Down the Wrong Path

During the sales cycle, software vendors usually present business cases showing paying for their product/services will have a positive ROI. They do this by:

Identifying problems in the customer’s organization

Quantifying the monetary impact of those problems

Demonstrating how features of their product solve those problems.

This is a strong argument. It demonstrates an honest interest of the vendor in the buyer’s company, an eagerness to partner on solving problems, and overall empathy. The problem is that this is a fabricated reality that oversimplifies the problem and paints the wrong targets that will likely persist through the deployment of the software. The complex process full of human-to-human interactions has now been distilled down to a handful of specific problems that a rigid “management” software solution can ostensibly solve.

Bear with me for a moment, as I take you through an example loosely inspired by my own experience.

Julius is responsible for payroll. As part of this role, he has to make sure recently hired employees are created in the payroll system. It takes Julius two hours every week to run a report from the separate HR system and load those employees manually into the payroll system. This manual process leads to errors and sometimes employees getting missed. especially when Julius is away. Alex, Julius’s team lead, is considering new payroll software and is won over by a vendor with strong integration3 offerings, especially with HR systems.

Three months and hundreds of implementation hours later, the new payroll system is setup with data flowing from the HR system. However, following one of the first payrolls on the new system, Alex is dismayed to hear a recent new hire was missed.

As it turns turns out, the “integration” brings only brings in an employee’s annual salary, not the biweekly amount. That still needs to be entered by Julius. When Alex tries to understand why this was not automated, they learn the first payroll amount is pro-rated by the number of days the employee was hired, but different divisions have different policies. Julius says he expects an email from the manager saying how much it should be and enter that. In this case, the manager never sent the information before the deadline.

A computer can only do so much when the process is still dependent on another human’s input. By oversimplifying the problem during the buying cycle, and falling for a fabricated reality of what “payroll management” involves, Alex has solved one part of the problem but fallen short of the desired outcome. Enterprise/B2B software implementations have dozens of these use cases where better is still not good enough. Functionality, designed and built at great expense, ends up as useful as a bridge that spans 90% of the way across a river but stops short of reaching the other side.4

Regardless of how strong vendor arguments for software’s capability for “managing” a process, the only way problems can truly be solved is by understanding the problems at their core. Once you do that, you’ll find “management” is too vague a word, and the exact solution you need will be obvious, and may not be new software.

So What Now?

This is about more than just a word (that we should stop using). To make software purchasing, implementation, and usage better, both for software vendors and customers, there’s some core principles everyone should accept.

Customers with complex business processes must accept that they’re going to end waterfall software implementation with a minimum viable product and a long to-do list of things learned from the project. Software implementation projects help hit a date, but getting the promised value from software requires a commitment to continuous, iterative improvement from those managing it.

Software vendors must focus on solving a core problem well, and not building to over-fit, tech debt-ridden customer solutions.

Customers must demand a solution from their vendors where the core 10x technology is obvious and idiot-proof, working even if the software is implemented and used by recent graduates with no experience in the process or industry.

Customers must ask vendors not just can a system support a process, but how. They must look past the simplified workflows in demos, and demand that they see examples of how the system reacts to change in the process, people, and data involved.

Customers must see true empathy from the vendor, and any other implementation consultants involved, for their employees.

Sales reps in B2B software present themselves as lifelines and gateways to the glamorous world of technology. They’re trained to find and empathize with the precise challenges this manager faces in their job. They share stories about how other leaders have transformed their business, and chart a path for growth and success in your role because of their software. Sales reps for smaller companies will present themselves as a Silicon Valley-esque success story that’s innovating the industry.

If the company likes their monolithic ERP provider then they probably go with that company’s point-solution-turned-suite-through-acquisition. Alternatively, the manager picks what they used in a prior job if they liked it. If they didn’t like it, they choose whatever is left.

"Integration" is another fraught word and the bane of many a software company.

Except in software, that last 10% is spanned by resources employed to make it seem like the bridge is actually there.